This post contains links to products that I may receive compensation from at no additional cost to you. View my Affiliate Disclosure page here.

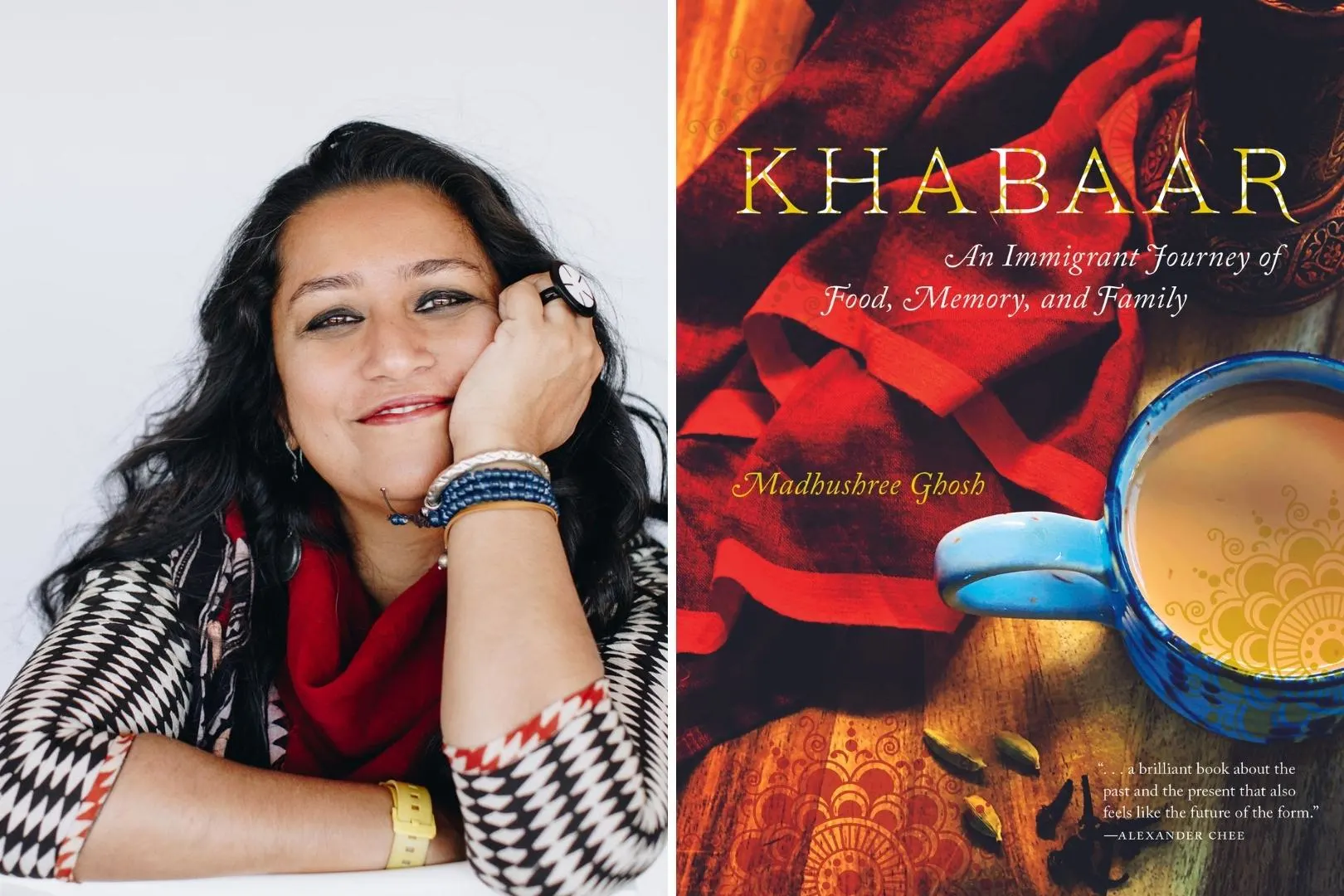

Madhushree Ghosh is the author of Khabaar, An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family.

Madhushree is the daughter of refugees, an immigrant, a woman of color in oncology diagnostics and an activist. Her nonfiction been published in The New York Times, Washington Post, Longreads, Bomb Magazine, Catapult, Guernica, The Kitchn, Serious Eats, The Rumpus and others. Her work has been awarded a Notable Mention (Best American Essays in Food Writing), Pushcart-nominated, an Oakley Hall scholarship and a Sirenland Positano residency (2020-21).

Khabaar is an expansion of Ghosh’s essay that received Notable Mention in The Best American Food Writing 2020, “At the Maacher Bazaar, Fish for Life” and weaves together contemplations on the diasporic experience through the eyes of food stall owners, household cooks, and professional chefs of color, asking a simple question: “What does it mean to feel at home?” – particularly through the foods we make.

Ghosh also examines her own immigration experience as a woman of color in science, a woman who left an abusive marriage, and a woman who keeps her parents’ memory alive through her Bengali food.

Relying on historical and anecdotal research on how food traveled, Khabaar addresses the question of what in food morphs when immigrants adopt another country? What stays the same and evokes the memories of a country long gone? What is passed down through the generations in the adopted country, making the cooking integrally immigrant cuisine?

Get to know Madhushree as she talks the process for crafting her memoir, her food research, key takeaways and more!

What are some of your favorite books?

Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction, by Arundhati Roy; Tastes Like War: A Memoir, by Grace M. Cho; Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity and Love, by Dani Shapiro and Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly, by Anthony Bourdain.

When did you know you wanted to become a writer?

I come from a family of freedom fighters, newspaper editors and politics-junkies from Bengal. My world has been discussing books, writing, discourse, debate and more of the same, especially at the dining table. I started writing (really bad) poetry that was published in the local newspaper when I was eight and continued throughout college in India—I think my mother was thrilled with seeing my name in print, and that was enough satisfaction to see her happy to keep going.

When I left India for graduate school in America is when I started writing in earnest—fiction mostly, and realized I need to learn craft, structure, narrative flow while telling what I’d call, very Indian stories. When I moved to nonfiction, it was really a continuation of the same style of storytelling, which is a combination of how we South Asians have grown up on folklore, parables, tales and mythological sagas-style of storytelling.

All this to say, that I’ve been writing since I was a child, but homesickness and a craving to keep India and my family’s stories alive along with social justice issues made me a writer while I continued my life as a scientist.

When crafting your memoir, how did you decide which elements of your life experiences to include?

I feel that’s usually the question any memoirist asks, i.e. what is relevant and why would anyone care? In a conversation with Girls At Library, memoirist and mentor, Dani Shapiro notes, “One of the things that I think is unique and interesting too on the level of the unthought known and what the unconscious is conscious of, is that my work serves as breadcrumbs. I don’t have to wonder if I knew this on some level. It is there.” This is, at the crux or any memoir, and/or narrative when we sit down to write our truth. I say ‘our’ because, it’s always our perspective we are representing the best of our ability and capability. What we have or what we have experienced, and how we have processed that information is what we write.

When I started Khabaar, or different versions of it, I was either living the experience or the aftermath of it. One could have written a chronologically relevant and accurate narrative. Or one could have taken instances of what the crux of what I was trying to communicate.

In Khabaar, the chapter, Orange, Green and White: An Indian Marriage, was the essence of why my marriage fell apart and how. I had written about it as a complete memoir, a four-hundred page manuscript and when it came to representing it in Khabaar, it was pretty obvious, at least to me, that it needed to be a less than twenty-page chapter in a book that was so much more than marital and emotional abuse.

Khabaar is more than that, but it also asks readers to think beyond a single linear story of immigration and women of color. We are multidimensional people, with views, visions and experiences that are universal and all these perspectives give us the option to start a conversation. I’ve crafted Khabaar with that hope.

Many people have a dish that reminds them of home and family. What are some of the dishes that bring back home for you?

I think it’s got to do with nostalgia and narrative and what memory triggers are for us in food. Really, every dish from home is comfort food because it reminds me of a time before this, a happiness that was joyous or an event that was momentous. To me, any time I made my Ma’s goat curry—where I substitute goat with lamb, or a simple moong dal with spinach, cumin/ginger seasoning in homemade ghee is what takes me back to 1976 New Delhi, when we had moved to the city, still trying to figure out our way, but together, united as a family.

Can you talk about some of your findings regarding how food changes when its adopted to another country?

Having a scientist background means that I can go down research rabbit holes and stay there for weeks! Researching how foodways and foods change as immigrants, migrants and indentured people adjust to their new or adopted homes and countries means I found out what they held onto and why, and how they innovated when there was a paucity of spices or resources.

For example, I myself adjusted my mother’s goat curry and use lamb instead. In South Africa, the Indian community in Durban created the bunny chow, a white bread hollowed out container to hold lamb or vegetable curry—a poor person’s easy-to-handle dish, or the Teh Tarik tea—a pulled tea creation from Malaysia, popular in Singapore, or the hearty thick black tea with spices and condensed milk, a creation of the Muslim Indian immigrants who worked or served the workers in the rubber plantation fields in their adopted countries.

To understand the enterprising initiatives, their ability to adopt and adapt to their new surroundings is a testament to the innovativeness of our people and how we have continued to learn and make do. Making do is certainly not as celebrated as it should be, in my opinion. And while we are ‘making do’, we are creating uniquely regional cuisine with a nod to our ancestral foods.

What do you hope are some of the key takeaways of your book?

I hope readers get to know more about my people—how we’ve lived, loved, learned and survived. I hope they see the universality of survival and thriving. That a childhood can be many things, but it’s that childhood that informs me, a scientist, a woman of color and an immigrant on how I hope to bring joy to my community in an adopted country. I hope Khabaar brings a smile on their faces, and they find commonalities in our experiences and I hope this starts a much needed conversation on why we matter.

What are you currently reading and what’s on your TBR (to be read) list?

This is such a rich question and I could keep at it forever! I like to read a few books a little staggered, but in parallel, so don’t be surprised by this list.

Currently, I’m finishing The 1619 Project created by Nikole Hannah-Jones and humbled by the work that continues to be done in this, and I just finished The Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, because, oh my goodness, this is greed, capitalism, privilege, whiteness, and science all rolled into one. In terms of food justice and food work, I can’t stop talking about National Book Award nominee Grace M. Cho’s Tastes Like War: A Memoir—a spectacular memoir on memory, madness and the love for a mother through food.

On my TBR list, is Vauhini Vara’s amazing The Immortal King Rao, Lidia Yukhavitch’s Thrust, out June 2022, Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man (August 2022).

Click here to order Khabaar on Amazon.