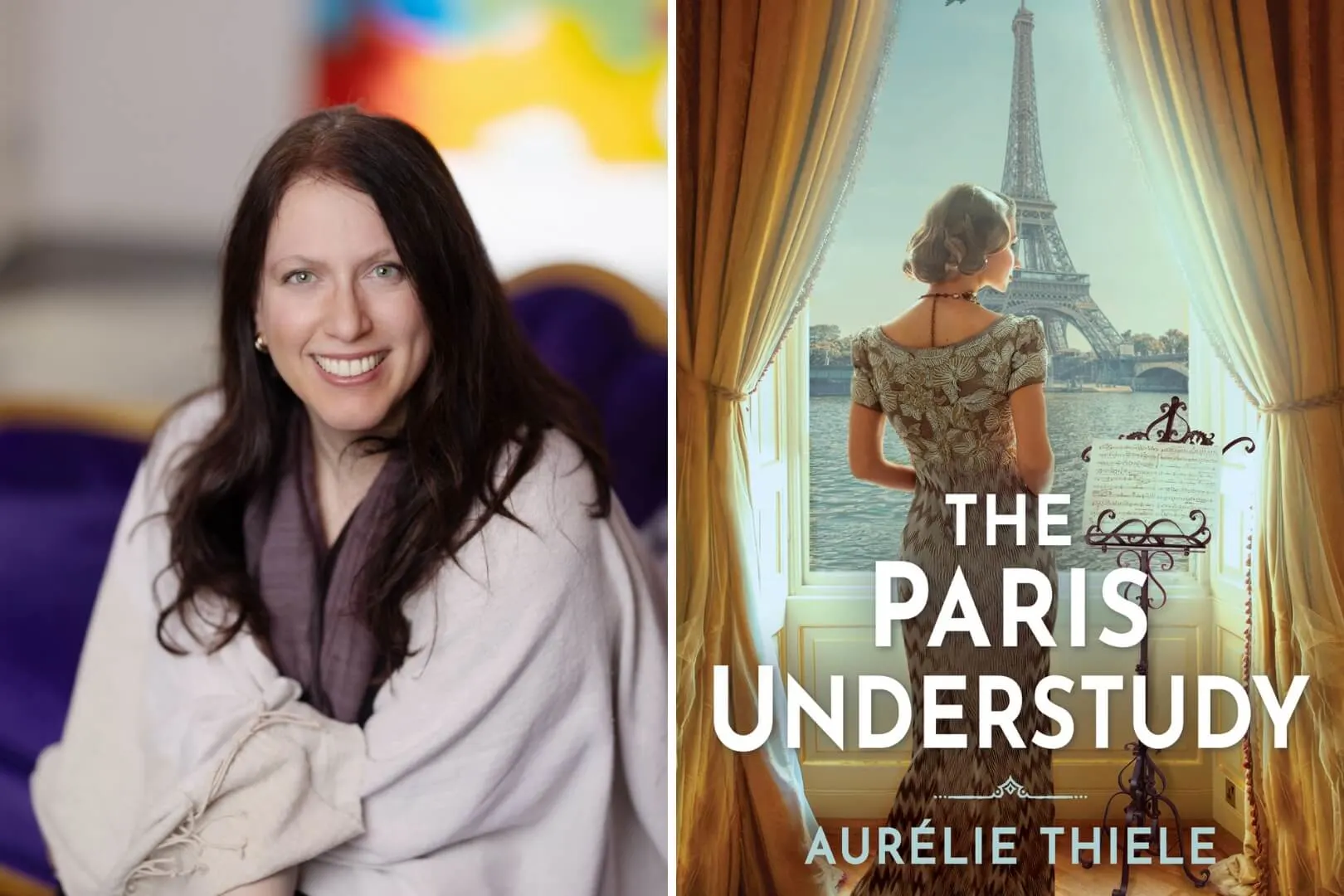

Aurélie Thiele is the author of The Paris Understudy, which is out now.

Aurélie Thiele is French American and lives in Dallas, Texas. She has studied writing at the UCLA Extension School and Bennington Writing Seminars.

The Paris Understudy brings to life the hard choices Parisians made–or failed to make–under Nazi occupation, in the tradition of Pam Jenoff and Fiona Davis.

Let’s get to know Aurélie as she talks favorite novels, story inspirations, her TBR and more!

What are some of your favorite novels?

In the historical fiction genre: The Winds of War by Herman Wouk and The Flight Portfolio by Julie Orringer. In the contemporary fiction genre: Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (I volunteer as a court-appointed special advocate for foster kids in Dallas County, TX so this book was particularly dear to my heart), Bel Canto by Ann Patchett (an opera singer thrown into a harrowing situation! I’m in awe of Patchett’s skill in the close third-person point of view), The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai (she most certainly knows how to deliver great emotional impact about a time where AIDS was a death sentence to many) and the Naples tetralogy started with My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante (I particularly like how she uses a mix of scenes and summaries, and key details to give us a sense of Naples and Florence, but also of course the evolution of the friendship between the main two protagonists).

Special mention to Red Rover by Deirdre McNamer, Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin, Horse by Geraldine Brooks, Preston Falls by David Gates, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, Nobody’s Fool by Richard Russo and Early Warning (Last Hundred Years: A Family Saga #2) by Jane Smiley.

When did you know you wanted to become an author?

Family lore has it that I started elementary school one year early because I wanted to learn how to read and write, but I was so young (I turned five the summer before I started first grade) that my parents had to take me to a specialist to get their approval. I was a quiet, solitary child and I loved to take refuge in the worlds of books from the start, and I would read a lot and write stories in my diary. But in school we only learned about dead authors, usually white males, and I only realized I could become a published author myself when I was about ten and some girl about three years older made the national news when she had her first novel published. From that point on, I never wavered in my desire to become a published author, and make other people discover worlds they hadn’t imagined before through my writing.

At first, I wrote in French, but after I moved to the United States for graduate school I decided to write in English. French and American audiences are very different (there is more of a market in France for plotless character-driven novels, for instance, and you can get published by famous presses without needing an agent, which changes the equation of how commercial the book should be to get in print) so it took me a while to figure out what sort of novel I wanted to write in English, but I’m glad I wrote something that resonated with my agent and my editor in my adoptive country, and hopefully many readers.

What inspired you to write The Paris Understudy?

Years ago, I learned about Germaine Lubin (1890-1979), the most famous French dramatic soprano of her time, highly esteemed for her interpretations of Wagnerian roles such as Isolde and Brünnhilde, but perhaps now most remembered for her associations with the Nazis—this includes singing at the Bayreuth Festival in 1939 when Adolf Hitler declared her to be an enchantress, and having an affair with a Nazi officer while Paris was occupied. (After the war, Lubin was tried for high treason, lost her French citizenship for a while, had to spend years with friends abroad, and was never able to resume her singing career, although she tried, and instead became a voice teacher.) She would’ve made an exceedingly bad novel protagonist, because she showed no character arc and no personal self-reflection whatsoever, having never expressed any remorse at associating with the Nazis.

I don’t think a novel’s main protagonists have to all be likable, but I do believe they have to be relatable, and wealthy and talented Germaine Lubin, who could’ve spoken out against the atrocities committed by the Nazis but didn’t do so, was not relatable to me at all. Instead, I chose to break the main parts of her personality into two different heroines in my novel: the accomplished but aging and childless star Madeleine Moreau and the striving up-and-comer Yvonne Chevallier who married at seventeen because she was pregnant with her son. (Germaine Lubin also had an only son from a marriage at a young age to a poet and chose divorce early on. Her son was sent to the front when war broke out in 1939 and she used her contacts with the Nazis to get him released. In contrast with Yvonne’s son Jules, though, he was not a concert pianist, did not join the Free French during the war, and committed suicide in 1953.)

I thought, what would make Yvonne associate with the Nazis? And I kept coming back to people down on their luck trying to play the only hand of cards they have and being rightfully crushed by history. In many ways she made the wrong choices, just like Germaine Lubin did. But I like to see in the character of Madeleine Moreau a side of Germaine Lubin that could’ve been her legacy to the world in this dark period, if she had done the right thing.

What was your favorite part or chapter to write?

I loved writing the beginning (especially the first three chapters of Part One) and the end (Part Three). The beginning was particularly dear to my heart because I’ve had it in this form for many years, and although I would edit out a sentence or two whenever I re-read it with a close eye, I knew it was basically set as the opening of my novel, so when I was losing heart about what came later in the book, I would find strength in the fact that the beginning worked, and if I could keep it going for, ahem, several tens of thousands words more, I’d have a really good book on my hands.

Regarding Part Three, I had some of it ready about the same time I had a good draft for the beginning, especially regarding Yvonne’s arrest and the trial. But the last chapter was hard to nail down. The first ending was: after Yvonne is released from prison, she sings in the subway, where Madeleine finds her. I was trying to make a nod to The Clown by Heinrich Böll, but my agent Betsy Amster felt it didn’t work, and with hindsight I realized she was right. You don’t want the very end of your novel to make a nod to any other work. The ending needs to be unique to stay with the reader. I won’t say what the ending is here to avoid spoiling it for readers, but I’ll mention that the characters of Madeleine’s husband Henri and Yvonne’s son Jules went through many incarnations. This is probably what made Part Two of the novel so hard to write: I knew the main plot from the start, but the subplots changed a lot.

Even for Part Two, which gave me such a hard time, there were parts I loved to write and nailed basically from the moment I drafted them. They were the chapters I added at the end of Part Two: the Vél d’Hiv roundup and the trip to Dijon. For most of the years I spent writing The Paris Understudy, those chapters didn’t exist. And then it became obvious I should add them, and hopefully your readers will understand why when they read them.

What drew you to the historical fiction genre?

I love imagining other worlds. Writing a historical fiction novel makes everything different: the clothing, the mores, the verbal expressions, the cars on the street, the songs on the radio, even the kind of radios and record-players protagonists could have in their living room. Of course, it can also lead to a rabbit hole where you spend the day looking at fashion in clothes, shoes and hairstyle in the 1930s. (The Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an amazing resource for that, and has plenty of pictures online.) Since we haven’t invented time machines yet, researching period details for historical fiction novels is the next best thing we have available to transport ourselves to different eras.

What are you currently reading and what’s on your TBR (to be read) list?

I’m reading Bring Up The Bodies by Hilary Mantel.

On my TBR list in fiction are Independent People by Halldór Laxness, The Memory of Love and Happiness by Aminatta Forna, Other Names for Love by Taymoor Soomro, Salt Houses by Hala Alyan. In nonfiction, I can’t wait to read Beyond the Handsomeness: A Biography of Thomas Schippers by Nancy Spada (Schippers was famous for conducting Antony and Cleopatra at the opening of the new Metropolitan Opera House in Lincoln Center in 1966, with Leontyne Price as Cleopatra, but his career was cut short by lung cancer, which he died of at age 47) and The Rulebreaker: The Life and Times of Barbara Walters by Susan Page.